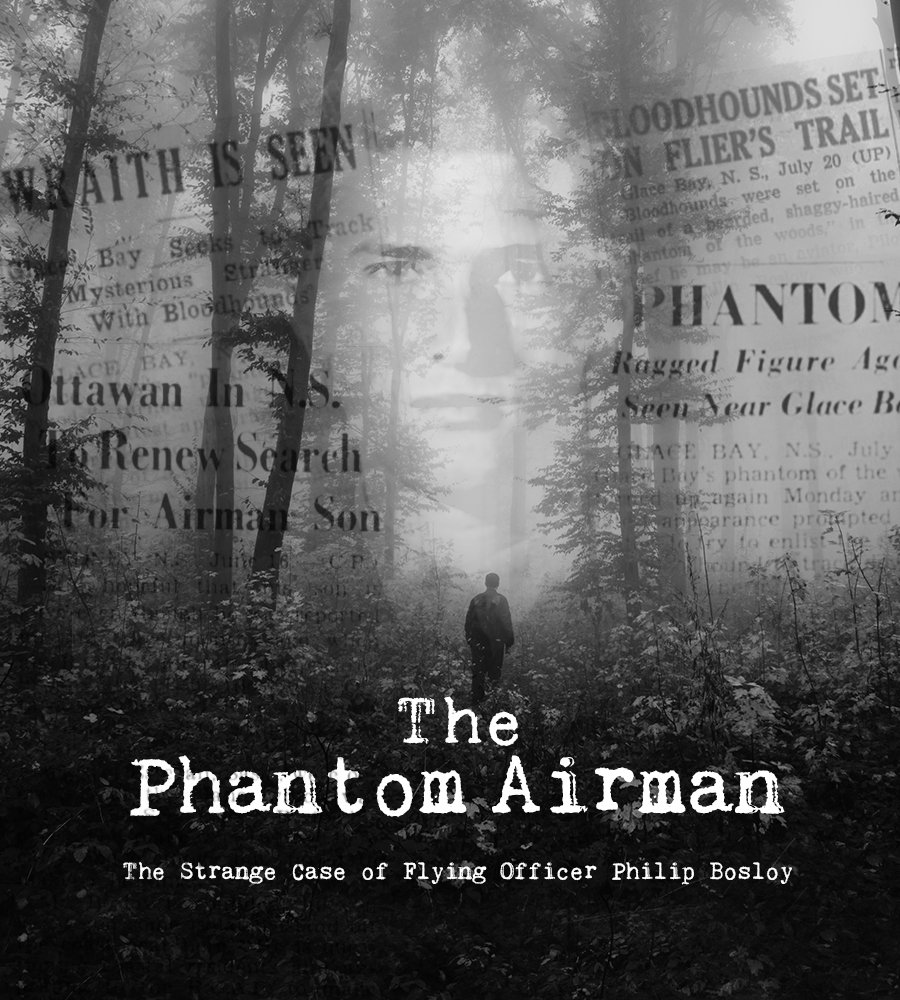

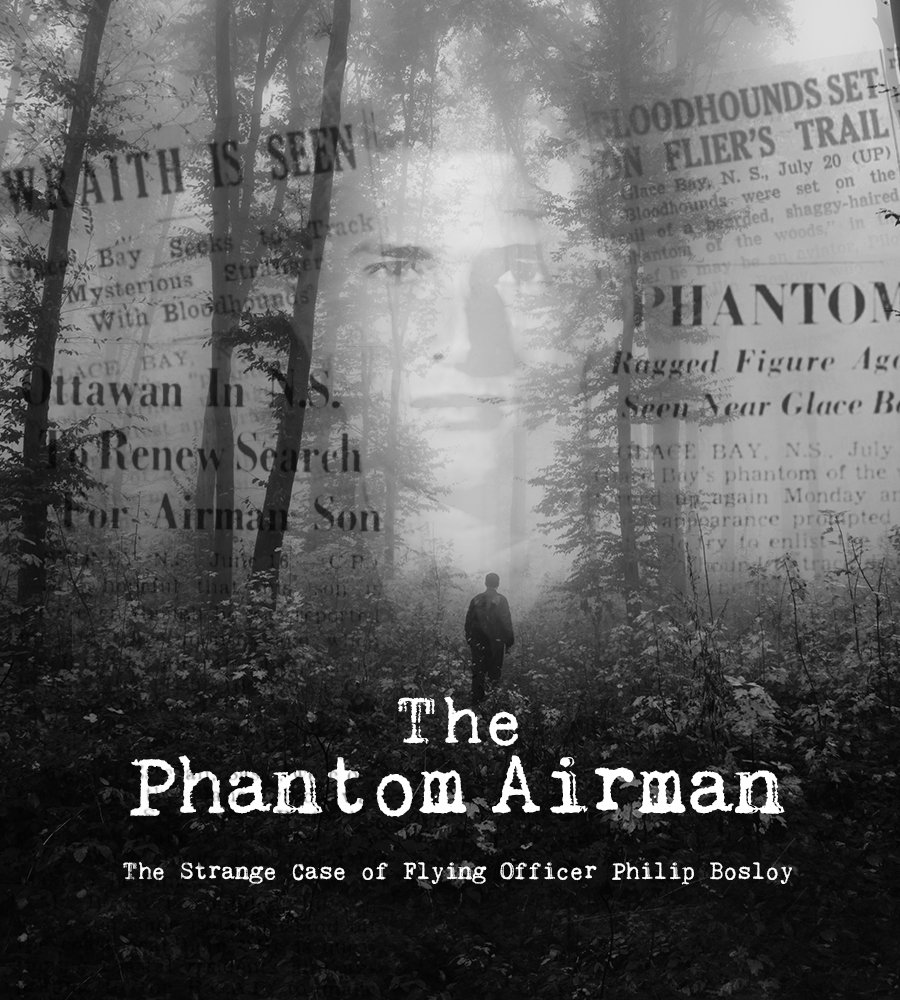

The Phantom Airman

Illustration: Dave O’Malley

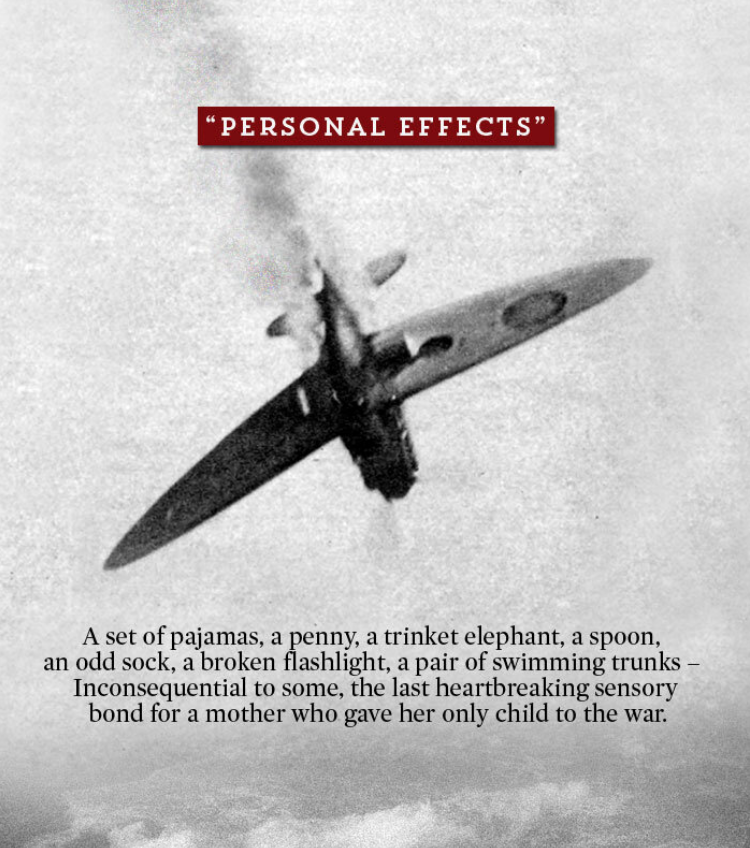

In the early and mid-20th century, parents let their children roam the streets without supervision, coming home only when the sun went down. They had no sympathy when you got “the strap” at school. They might even give it to you themselves for good measure. There was no snowplow or helicopter parenting. All obstacles in your life were yours to get over. They were your parents, not your friends. They expected you to find a paying job as soon as you became a teenager and they didn’t say “Follow your dream” when you announced that you wanted to be fashion influencer. If you wanted to go to university, well, that was fine. But you had better get a good part-time job to pay for it. They expected and even needed you to leave home as soon as possible, and never come back.

Over 500 sets of parents in my downtown neighbourhood lost sons in the five-year span of the Second World War. Some lost two. Most would never see them again or have the chance to visit their graves. Many knew nothing of the manner of their deaths. Closure was not an option. There was no spectacle of grief. No counsellors to rush in. No disorder to diagnose in the aftermath. Because of all this, people today make the sad and somewhat arrogant assumption that folks in the 1940s didn’t love their children as deeply as modern parents do now. Those people are dead wrong.

During the war, the death of a son on air operations was a heavy and lacerating blow to every family, but back then it was often drawn out for many months, revisited again and again as each layer of hope was stripped away after the first missing-on-operations telegram. Absolute disappearance was, as often as not, the unsatisfactory reality that parents would have to embrace for the rest of their lives.

On the cloistered walks of the Runnymede Air Forces Memorial west of London, there are inscribed the names of 20,456 men and women of the Coomonwealth air forces who were lost in the Second World War during operations from bases in the United Kingdom and North and Western Europe, and who have no known graves. Over 3,000 of those names are Canadians. Most were lost to the sea, some remote lakes, and some on a nameless mountain side. The Ottawa Memorial here in Ottawa commemorates the names of nearly 800 young men and women who lost their lives over Canada or its territory and have no known grave. That’s 800 people who disappeared in five years in Canada—into the seas, the lakes, the wilderness. The Malta Memorial in Valetta Harbour carries the names of 2,297 airmen who disappeared, 285 of whom were the sons of Canadian families. Young airmen from Ottawa are listed on all of these memorials.

All of us are recently familiar with the strange disappearance of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370, which mysteriously vanished in 2014. The event spawned documentaries, books, strange conspiracy theories, and a 30,000-word Wikipedia page. The search for answers and the wreck site continue to this day with billions of dollars spent and search crews continuously at risk. All because people demand answers and hang on to the very finest filament of hope.

The Fruit Vendor’s Son

Handsome Philip Bosloy was born in July, 1920, the son of a hard-working grocer in the Ottawa suburb known as the Glebe. He grew up surrounded by the warmth and expectations of his extended Jewish family. He attended the same elementary schools my daughters and son attended — First Avenue Public and Hopewell Public.

Expected to be involved in one of the family businesses or start his own, Philip enrolled after elementary school at the Ottawa High School of Commerce, which was co-located with Glebe Collegiate Institute. After two years of bookkeeping, typing, and other commercial courses, he moved in 1935 to Ottawa Technical High School where he studied electrical and machine shop work, graduating when he was just 17. He had two older siblings, a sister Mary and brother Jack, and a younger brother by the name of Sydney. Both his parents were recent immigrants from eastern Europe. He loved to draw and enrolled in a correspondence course in illustration from the Federal School of Applied Cartooning, a Minnesota-based company that employed instructors including future stars Charles Schultz (Peanuts) and Mort Walker (Beetle Bailey). It was the kind of course advertised in comic books and on matchbooks. He also loved sports, including tennis and skiing, but especially basketball and softball.

His father, Louis Bosloy, was born Louis Boguslavsky in Kiev, Ukraine (though this was called Russia in Philip’s attestation papers), and his mother, Chawa Gosewitz, was also from an unstated location in Russia. They married in Ukraine and came to Canada in 1913. Louis operated a small grocery shop called the Empire Fruit Store below the family home at 885 Bank Street. The Members of the extended family also operated a radiator and auto repair shop from the same building. They were a close-knit, industrious family with strong ties to the local Jewish community, many of whom were recent immigrants themselves and had recently fled the spread of communism and the approaching creation of the Soviet Union.

A wonderful photograph from the Ottawa Jewish Archives of a family group that includes members of the Bosloy family, as well as the Gosevitz (Gosewich) and Friendly families, who were connected by marriage. Taken in 1929 in Ottawa, we can see a bright, shining nine-year-old Philip Bosloy at the back on the far left. Sitting second from the right is Philip’s devoted father Louis. In the back row, standing fourth from the right is Chawa (Eva) Bosloy (née Gosewitz), Philip’s mother. Standing sixth from the right is Mary Bosloy, Philip’s sister. Sitting in front of Philip at the far left is Philip’s older brother, Jack. Photo: Ottawa Jewish Archives

A 1950s photo of the Bosloy family place of business at 885-891 Bank Street. Here, in the building they owned, the Bosloys and Gosewichs operated the Empire Fruit Store (where we see the Export cigarette sign) and Excel Radiator Repair (garage at rear). The lot of the United Car Market, a Studebaker dealership, has been the site a Mexican restaurant since the late 1970s. Having spent a half century in this neighbourhood, I know every one of the buildings in this photo intimately and never knew the sad tale they held. Photo: historynerd.ca

885 Bank Street today is the home of Irene’s Pub, an Ottawa live music icon. Next door at 887 is the Glebe’s favourite barber — Ernesto’s. In the 1940s, Phillip Bosloy used the address of his family’s business, the Empire Fruit Store, as his mailing address. The Bosloy family lived above the store. The upstairs apartments are accessed through a door at 889 Bank Street. One of my best friends lived in the former Bosloy apartments in the 1970s and 80s and I visited there many times, drinking espresso and cognac. My former wife also operated an architectural practice in the basement of the building. Jack Bosloy, Phillip’s brother, operated a radiator repair shop and garage in the back until the late 1970s. I did in fact meet Jack when he was working on my friend’s Volkswagen half a century ago. Photo: Google Street View

Philip enlisted in the RCAF in June 1941, and following his time at Manning Depot, he was sent down to Debert, Nova Scotia, for guard duty at No. 16 “X’ Depot, an RCAF ammunition storage facility. His next stage in becoming an airman was Initial Training School (ITS) where, following a series of academic courses and airmanship studies, he would be judged whether he was suitable for an aircrew position. While at No. 3 ITS in Victoriaville, Quebec, a second medical assessment (the first was at enlistment) was carried out in October. The examiner’s notes revealed an underlying soft racist vein in the medical officer, one which, I have noticed, can be detected from time to time in service files. A handwritten note in the “History of Present Condition” states: “Quiet, mild, not aggressive, Jewish lad of not more than average intelligence and initiative.” Nowhere in the files of Anglo-Canadians have I ever seen “Scottish lad” or “Christian lad” written to describe anyone. Somehow, the examiner felt compelled to add this irrelevant information, which was already supplied by Bosloy himself in his attestation papers. All were required to identify their religion then so that it might be added to their identity discs in the event of last rights and battlefield burial.

Aircraftman Second Class Philip Bosloy’s file photograph from Manning Depot depicts a handsome young man with dark hair and penetrating green eyes. Photo: Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Bosloy’s results at ITS were promising, graduating 32nd (ITS classes were usually large) with an average of 82%. But his flying instruction results were well above average. He came fifth in his Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) class at No. 11 EFTS, Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Quebec. After graduating there in January 1942, he was posted to No. 13 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) at St. Hubert near Montreal, Course 47. His course included 19 recent graduates from No. 11 EFTS, comprising seven Canadians and 12 members of the Royal New Zealander Air Force, as well as several members of the Royal Air Force. To his credit, his name does not appear in the school diary — this was not the case for student washouts who “CT’d” (Ceased Training) and those who damaged aircraft or flew outside the regulations.

As his SFTS course was coming to a close, he made application to the school’s commander on April 15th to marry his sweetheart Ida Gordon. Ida was the daughter of Julius and Minnie Gordon, Russian immigrants from Galicia before their arrival in Canada in 1912. They lived in Ottawa’s Lower Town neighbourhood with many other Ukrainian Jewish families and operated a corner convenience store at 108 O’Connor Street, an area of town long since obliterated by high-rise towers. To back him up, Philip had letters of reference for his fiancée from Rabbi Oscar Fasman, and from her employer, A. W. Bannard, Acting Chief Treasury Officer for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). Rabbi Fasman stated that Ida was “a member of a well-respected family in this community and I know her personally as a young lady of excellent character.” Bannard stated “without reservation that Miss Gordon is very highly thought of by this branch.” Since Bannard’s branch paid the bills for the BCATP, that reference certainly had weight for the commander of No. 13 SFTS. In a less-than-romantic statement, the school’s commander Group Captain J. Stanley Scott, MC, AFC, approved the marriage stating “This airman is eligible in all respects to be granted permission to marry in accordance with the King’s Regulations (Air) Paragraph 1360.” Ida and Philip were married in Ottawa on Monday the 4th of May. His brother Jack stood in as his best man and Mary, his sister, as Ida’s bridesmaid. Their honeymoon took them to Montreal where the highlight would be Philip’s wings parade two days later.

He graduated third in his class of 25 remaining students on May 6th with Louis and Chawa no doubt making the short train journey to St. Hubert to join Ida for his wings parade. Upon graduation his stellar performance earned him a commission as a Pilot Officer. He was granted ten days’ leave, likely going home to Ottawa with his new wings, new pilot officer’s epaulettes, and new bride.

Out on the edge of Canada

In the winter of 1943, the weather in Maritime Canada was much the same as it is today — cold, wet, and miserable. Beautiful days were rare and weather systems charging in from the south and west could obliterate visibility in a matter of minutes. One moment you were cruising along with the coast in sight and the next you were descending under a heavy load of ice looking for a glimpse of anything — a road, a rail line, the coast, or even the ocean. If you weren’t careful, you could lose your way and find your death.

After getting his wings, young Philip Bosloy was posted as a staff pilot to perhaps the most unglamorous flying unit in the Royal Canadian Air Force — No. 4 Coastal Artillery Co-operation Flight (4 CAC) — a tiny unit stationed at remote RCAF Station Sydney at the northern reach of Cape Breton Island. Equipped with three National Steel Car–built Westland Lysanders, their task was simply to fly up and down the Atlantic coast of Cape Breton spotting for coastal artillery batteries like those at Fort Lingan, Fort Oxford, Chapel, and Stubberts Points along the mouth of Sydney Harbour, and towing target drogue lines for coastal anti-aircraft batteries to shoot at. These coastal defence batteries (eight in all) were built to protect Sydney’s mines, steel factory, naval docks, and shipping basin. Bosloy and his fellow pilots were also tasked with Harbour Entrance Patrols. From time to time there was photographic and recce work as well as the odd missing aircraft search. The work was unrewarding and far from the fighting fronts they all signed up for. Staffing at 4 CAC in the early months of 1943 included three officers, three aircrew airmen, and 11 ground personnel.

As soon as he was settled, Bosloy sent for Ida to join him in remote Sydney, Nova Scotia.

A map of the Army and Navy’s coastal defences. The soldiers and sailors manning these artillery emplacements were kept sharp by daily practice. Their targets were drogues towed by the Lysanders of No. 4 Coastal Artillery Co-operation Flight, which also spotted shot for the larger calibre guns. Map by author and Google Maps

Bosloy, still a Pilot Officer, posted in to 4 CAC mid-May 1942, but was immediately and temporarily detached to the much larger No. 2 Coastal Artillery Co-operation Flight (2 CAC) at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, for training on the Lysander. Bosloy had his familiarization flight on the 18th, followed by plenty of practice flying and some time in the Dartmouth Station Link trainer. By the end of May, he was flying Anti-Aircraft target towing lines near Dartmouth. On the 14th of June he ceased his detachment to 2 CAC and was transferred back to 4 CAC to begin operational flying.

Not much happened at 4 CAC. While Bosloy’s work was not taxing, the weather made it dangerous. The Lysander was a sensitive aircraft to begin with, but the moisture and cold played havoc at the station. The station itself was shut down from time to time due to heavy snow drifting on the runways, fog, blizzards, sleet, and heavy rain. There were days during January and February when none of unit aircraft was serviceable. The only excitement in January happened on the ground when two RCAF armourers were working on Lysander 488. While testing the starboard Browning machine gun — housed in the wheel fairing — out on the ramp, the gun “ran away,” firing between 300 and 400 rounds and shooting up the hangar door.

Things got a little more serious whenever convoys were leaving or approaching Sydney harbour. Then, Bosloy’s Lysander might be equipped with small bombs slung from stubby winglets protruding from the wheel struts and .303 ammunition to feed the light machine guns in the wheel fairings. Not the most formidable armament but, still, he would be ready if he found a German submarine lurking about the harbour mouth.

As well as their target towing duties, pilots of 4 CAC practiced dive bombing and machine gunning. Bombs were carried under small winglets protruding from the wheel housing. The machine guns were also housed in the landing gear and fed by belted ammunition in the gear leg (above). It was not a formidable array of firepower, but it might give pause to a U-boat commander considering coming to the surface along the coast. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

Chapel Point Battery at the mouth of Sydney Harbour. As this was a large-calibre gun fort, Philip Bosloy and other 4 CAC pilots and radio-operators would spot artillery shot and radio adjustments to the gunners in the fort. Photo: Atlantic Memorial Park Society

The Stubberts Point Battery was a harbour defence gun on the northern shore of the wide entrance to Sydney Harbour. The battery employed a quick-firing Twin Barrel Six-pounder Gun, seen here in its steel turret during the Second World War. These semi-automatic loading, duplex guns could pour out 70 rounds per minute — enough to deter any raider on the surface.

A convoy of merchant ships assembles in Sydney Harbour, one of the major terminals of the North Atlantic convoy system in the Second World War. It was 4 CAC’s duty to keep the coastal artillery batteries that protected the harbour sharp by providing ranging information and target drogue towing. Photo: Atlantic Memorial Park Society

Another photograph of Sydney Harbour with the submarine net and gate boat in the foreground and dozens of cargo ships anchored beyond. Photo: Beaton Institute Digital Archives

Troublesome Lysander 459

Lysander 459 on the Ottawa River after test landing on skis. There was a small ski where the tail wheel was, but we can see that if the tail sank any lower, there could be a chance of damage to the horizontal stabilizers depending on the snow’s consistency.

On January 25th, 1943, 4 CAC’s commanding officer Flight Lieutenant Gordon W. Appleby of Chilliwack, British Columbia, and Flight Sergeant Fulton left on the evening train for Montreal and RCAF Station St. Hubert to pick up Lysander 459 and ferry it back to Sydney. Recently modified to tow a target drogue, it was replacing Lysander 456, which was giving them endless troubles and was unserviceable much of the time. At 4 p.m. on the 28th, they left Montreal to return to Sydney with the replacement Lysander, staying the night in Millienocket, Maine, before setting off for Sydney the next day, arriving well after dark on the 29th. The “new” unit aircraft was closely inspected for acceptance by ground crew the next day. The squadron ORB tells us how disappointed the service personnel were with the state of the aircraft: “Lysander 459 appears to be in very bad shape, according to Maintenance. Apparently it is in need of a general overhaul.”

Lysander 459 was previously in the employ of two RCAF Station Rockliffe-based units—briefly with the School of Army Co-operation and then with Test and Development Establishment. It was modified to land on skis (the only RCAF Lysander to use skis) and tested at Rockcliffe and Porquis Junction, Northern Ontario, over the winter of 1941-42. In April its pilot, Flying Officer D. Armstrong, undershot a landing at Rockcliffe and the Lysander suffered Category “C” damage. Assigned to Eastern Air Command and 4 CAC, it was modified to target towing standards, but had seen some abuse over its previous two-year career.

Lysander 459 tied to the ice on the Ottawa River when it was operated by the RCAF’s Test and Development Establishment at RCAF Station Rockcliffe. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

On February 8, after maintenance did what they could, Lysander 459 flew its acceptance flight. It was found satisfactory except for the fact that it dropped 150 rpm when changing from Auto-rich to Auto-lean. On the same day, Bosloy began a 14-day leave – likely coming home to Ottawa with his wife Ida to warm themselves in the love of Louis and Chawa, Julius and Minnie, eat some traditional and home-cooked meals, and catch up with Ottawa friends.

Two days later, Lysander 459 “threw its oil” when starting up in the morning on the frozen ramp at 4 CAC, leaving only two aircraft serviceable. Like Lysander 456 which it replaced, 459 was unreliable and seriously impacting the operational capacity of the unit. The aircraft continued to have problems with its mixture and a call was made to No. 4 Repair Depot (RD) at RCAF Station Scoudouc, the major aircraft repair facility for Eastern Air Command.

On February 22, Philip and Ida returned from Ottawa. After reporting in with Appleby, he was likely glad to hear that orders came through to take the recalcitrant Lysander 459 to Scoudouc for a carburetor jet modification. Flight Sergeant John Joseph Slabick, also recently back from a two-week leave, would accompany him as his radio operator. Bosloy, the son of a Ukrainian immigrant, and the Polish Slabick, were both of east European backgrounds and had flown together on many occasions. Just back from leave, they were likely happy to be doing something interesting like a Maritime cross-country to get back in the swing of things. That night Bosloy and Slabick attended a hockey game in Glace Bay where the RCAF team defeated the Navy 4-2. According to the ORB, former 4 CAC airman Sergeant G. E. Montani played a “briliant” game. Afterward, Slabick returned to the station and Bosloy headed to the apartment he and Ida shared.

Philip and Ida rented an apartment off the station at 140 Brookland Street in Sydney. Photo: Google Maps Streetview

Slabick was from the bucolic-sounding Summerberry, Saskatchewan, the son of Frank and Victoria (Natushko) Slabiak, Polish immigrants. He had three brothers and two sisters and had lived in Southern Saskatchewan his entire life where he was an “air conditioning and refrigeration service engineer.” As in Bosloy’s service file, I could detect an undercurrent of bigotry for Slabick’s Polish background in his assessment after washing out of flying training at No. 5 EFTS in High River, Alberta.

“A young Polish boy, who failed because he probably got a little lazy and forgot to apply himself to his ground work. He is not overly keen about the air, but states “He likes it well enough.”

Again, there seems no need to add the Polish adjective to his assessment and, in my opinion, the writer implies a connection between Polish-ness and laziness. It is interesting to note that Slabick had applied to change the spelling of his name from John Slabiak to John Joseph Slabick, a name which he used when he enlisted. Perhaps this was an attempt to reduce the “Polishness” of his name. His father’s name was still Slabiak in his attestation documents, but towards the end of the war, when Frank was dealing with National Defence regarding his son’s estate, he used Slabick — perhaps to smooth out the bureaucracy.

The crew for the ferry flight of Lysander 459 to Scoudouc and back would be Flying Officer Philip Bosloy, pilot, and Flight Sergeant John Joseph Slabick, wireless operator. Photos via Canadian Virtual Wwar Memorial

Tuesday, February 23 at RCAF Sydney dawned a rare perfect flying day in the Maritimes with CAVU (clear) skies and light winds noted in the 4 CAC diary. Bosloy and Slabick’s flight would take them 230 miles due west to RCAF Station Scoudouc, east of Moncton, New Brunswick. In addition to operating as a relief field for Moncton’s busy No. 8 SFTS, it was the home of No. 4 Repair Depot. Here they were scheduled for a quick modification to 459’s carburetor and then a return flight to Sydney the next day. The work was scheduled for early the next morning, so the two men took off at 2:30 in the afternoon and landed at RCAF Station Scoudouc 2.5 hours later. Their flight time suggests they likely did not take the direct route, and though the cruising speed of the Lysander was rated at 170 mph, they were probably cruising at 145-50 mph. They likely remained close to the Northumberland Strait coastline of Nova Scotia in the event that Lysander 459’s poor performing Bristol Perseus XII engine gave out on them. The icy February waters of the strait promised a short life to RCAF crews operating above.

Though Scoudouc lay 230 miles due east, it is likely that Bosloy and Slabick remained along the coast of Northumberland Strait for safety reasons. The blue line depicts a possible track for their flight to and from Scoudouc.

The two young fliers must have thoroughly enjoyed the scenic flight along the coast of Nova Scotia, with Prince Edward Island far off on their starboard side the whole trip. Ice would still be clogging Northumberland Strait and with clear skies, the landscape below would have been a brilliant blinding white. The two had flown together on numerous occasions in the past months, even in Lysander 459. Bosloy and Slabick arrived in perfect weather and, upon checking in at the operations room at Scoudouc, telephoned Sydney to let them know they were safely down at 4:45 p.m.. The 4 CAC duty sergeant duly recorded it in the diary.

It was a busy day as always at No. 4 RD, with aircraft coming and going from all over Eastern Air Command — Bolingbrokes, Harvards, Ansons, Hudsons, Norsemans, and even a Handley Page Hampden. Typical of the work at No. 4 RD, a Lockheed Hudson VI (FK443) was flown in from Port Hawkesbury on the Cape Breton shore of the Strait of Canso by staff pilot Flight Lieutenant G. F. Gilbert. The Hudson, assigned to 31 Operational Training Unit at Debert, Nova Scotia, had force-landed on a 700-foot high ridge line four miles inland from Port Hawkesbury. The aircraft was removed from the ridge and brought through the bush to the frozen surface of the strait near Port Hawkesbury. It was put back together with a new engine installed along with two new propellers. Some temporary repairs were made to the nose and the aircraft braced internally. Then Gilbert took off from the ice and brought it back to Scoudouc for repair.

Lysander 459 was signed over to the mechanics and towed indoors to thaw out. Taking their kit with them, they split up, Bosloy enjoying more comfort in officer’s quarters while Slabick headed towards the NCO’s quarters. Unknown to Slabick, he would get a promotion to Warrant Officer II a week later. Perhaps they got together that night in the recreation hall for the screening of the crime drama The Glass Key, starring Veronica Lake, Alan Ladd, and Brian Donlevy.

Lysander 459 was ready by noon the next day. Bosloy checked the weather in the Sydney area before taking off at 4 p.m. that Wednesday by placing a telephone call to Moncton. They were told that the weather at Sydney was expected to be “alright” until about 7 p.m.. Their flight plan had them arriving in Sydney at 5:45 p.m. with a strong tail wind. They had 95 gallons of gas aboard and an all-up weight of 5,763 lbs. They took off expecting to beat bad weather into Sydney. They were never seen again.

Despite the promise that they had open weather at Sydney until 7 p.m. that evening, local weather records indicate that by 5:50 p.m., the ceiling was down to just 400 feet and the visibility down to four miles in smoke, haze and rain. Just 15 minutes later, fog began to roll in and by 6:30, the ceiling was at 200 feet and visibility down to just 3/4 of a mile.

At 7:30 p.m. on February 24, Flight Lieutenant Appleby was called and:

“advised by Operations that F/O P. Bosloy and F/S J. J. Slabick were one hour overdue in Lysander 459 from Scoudouc [actually by then it was 1.75 hours-Ed]. Efforts, made by the Station, to contact this aircraft by radio were without success. Later during the evening when P/O P. Bosloy's estimated supply of gasoline was believed to be exhausted a broadcast over the radio was made, asking all persons who had heard or seen an aircraft in the vicinity to report such an occurrence to this Station. A number of reports came in but nothing really definite could be learned from them.”

On Thursday, the base was buffeted by strong winds and snow all day. Despite this, Appleby took off at 8 a.m. (sunrise) to search for the missing aircraft and his two friends. By 9 a.m. he was forced to return due to freezing rain. The rain turned to snow, which continued until 5:30 p.m. that evening. The unit diary expressed the frustration that the other pilots and men felt as they sat out the storm: “Waiting for the weather to clear has not been too easy on the personnel of this Unit.” The Sydney Station diary entry for Thursday states that the next-of-kin were notified that the men were missing, but Ida must have known already since Philip did not come home as planned the night before.

On Friday the 26th, the weather was clear and cold, but the unit had only two Lysanders left to search with, and one was not serviceable. Appleby, who always, it seems, took direct responsibility for the search, was up again at 8 a.m. With only one serviceable aircraft and only two pilots, 4 CAC still managed 14 hours of search time that day, but came up empty. Aircraft from the station’s other units joined them — 119 (Bomber Reconnaissance) Squadron’s Bolingbrokes managed 27 hours flying search time, while 128 Squadron put their Hurricanes up for a total of 38 hours searching time. The diary states that “The entire island of Cape Breton was covered by aircraft from this base but no trace of the missing A/C was uncovered.”

Radio Direction Finding (RDF) plots from Slabick’s transmissions indicated that they were, for a while, south of Sydney, out over the Atlantic at 5:22 p.m. and that Bosloy was flying “on various courses over the sea,” finally coming over land at 7:06 p.m. and passing close to Sydney Station and “practically over Sydney.” Bosloy, flying blind in the fog and rain, could not identify ground and, eventually running out of fuel, went down in the sea somewhere. There is another factor not mentioned in the inquiry report and that may have played a role. The weather conditions that evening were perfect for generating rime icing on the Lysander’s flying surfaces and propeller. Perhaps the build-up of ice through an hour or more of flying in the cloud caused them to stall while over the sea. Slabick had been broadcasting on 4 CAC’s frequency, but failed to instruct the Sydney wireless operator or any other wireless station of this, and as a result the Sydney operator was only monitoring the guard channel. Slabick’s log book showed that he had only made one other cross-country flight since he entered the service — that one to Scoudouc and back as well. Investigators would later remark that he was unfamiliar with cross-country procedure. Of course, none of this was known until later. In the end, not much could be determined about their fate and they would, in part, blame the disappearance on the crew’s inability to establish and maintain solid radio communication with Sydney.

The waterfront of Sydney, Nova Scotia around the time of the Second World War with its steel plant and collieries. Philip and Ida’s apartment was near the extreme right side of this photo. Photo: Beaton Institute Digital Archives

4 CAC and other units based at Sydney continued to search whenever the weather and serviceability of aircraft permitted, which seemed like every second day over the next week. A week after they disappeared, there was a report that “lights were seen last night flashing on Gillis Mountain just west of Gabarus Bay — along south shore of Cape Breton Island about 35 k south of Sydney,“ and an aircraft was sent to investigate. With no result following a two-hour search, the ORB stated “Hope for the safety of F/O Bosloy and F/S Slabick grows rapidly less.” Slabick’s in absentia promotion to Warrant Officer was also noted.

The next day, the ORB lamented the unit’s weakened operational situation, which limited their ability to search for their comrades or do the job they were designed to do:

“This unit is very short handed as regards aircrew at this date, we are short one pilot and two Wireless/Air Gunners. So far no reply to our signal for replacements has been received. The last of the monthly reports were mailed away today. Aircraft serviceable: One”

After just the one week, 4 CAC began to refocus on its operational duties and no more searches were conducted. Less than two weeks after Lysander 459 went missing, the detachment received instructions on writing off Lysander 459 and its contents. This was followed quickly by the arrival of Slabick’s replacement wireless operator and then two days later Bosloy’s replacement.

On the March 13, two and a half weeks after the disappearance of Bosloy and Slabick, some pieces of a life preserver were found washed up on the Glace Bay beach as well as components thought to be a portion of a parachute. These were examined and identified by Appleby as possibly coming from Lysander 459. In the last weeks of March, the unit began investigating better life preservers and inflatable single-person “K”-type dinghies. Clearly, the unit was rattled by Bosloy and Slabick’s loss and the likelihood that they came down in the icy Atlantic in February. The very last entry in the unit’s ORB for March 1943 states with finality that Bosloy and Slabick were “missing from Air Operations since 24th of Feb. 1943.” Their names do not appear in the ORB for two and a half months, but then…

I have a dream.

Throughout April, the unit returned to normal operations. Men came and went. The weather continued its capricious character. Drogue lines were towed. Victory bond drives raised money for the war effort. Aircraft were worked on and serviceability began to improve. Men practiced with their pistols on the range. Photo recce tasks and cross-country flights broke the monotony. The trauma of Bosloy and Slabick’s disappearance began to fade.

But not in the Bosloy household. Grief consumed Louis and Chawa. Ida moved back home from Sydney to live with her parents on King Edward Avenue in Ottawa’s Lower Town neighbourhood. The stress of the past two months began to distract Louis. In April, Louis was pulled over by the police when he failed to stop at a stop sign. He appeared in court on May 4 and was fined $1 plus $2 costs. In June, he began to have dreams about Philip, in which his son appeared to him and told him he was alive. Louis was both distressed and buoyed by the sight of his son in his sleep.

In mid-June, Louis, unable to take waiting anymore, left his Empire Fruit Store in the hands of his family and bought a train ticket at Union Station to take him to Sydney, the far away place where his son had been stationed. Sitting in his brocaded seat, looking out the window of the train as he crossed Alexandra Bridge over the Ottawa River on his way to Montreal, he could see the great pans of softwood logs floating on the river, or being fed to the cordillera of pulp logs at the Eddy paper mill. He had not travelled since coming to Canada, and the length of his journey was daunting, but so was a future without his son. He changed trains in Montreal, and soon was rolling northwest down the shore of the St. Lawrence River, as fundamental to Canada’s identity as the Dnipro River was to Ukraine’s.

A day later, as his train turned southeast, following the depth of the wild Matapedia River Valley as it cut across the ancient mountains of la Gaspésie, he must have had an overpowering sense of the majesty and enormity of the country he now called home — wild rivers and endless forests in which a man could stay lost forever. Every mile took him farther away from the comfort of family and yet brought him closer to assuaging his continuing nightmare.

At Truro, Nova Scotia, he changed trains again for the last two hundred miles, travelling on the old Intercolonial Railway system through New Glasgow to Mulgrave on the west shore of the Strait of Canso. Here his passenger car was shunted onto a massive railway ferry for the short voyage across to Port Hawkesbury where another locomotive was waiting to pull them to Sydney.

There is no indication in any records that Louis Bosloy had informed Philip’s unit that he was on his way. It appears that on June 16, 1943, a grey and rainy day, a heavily accented man presented himself at the guard house at RCAF Station Sydney, and asked to speak to Flight Lieutenant Gordon Appleby. He likely knew Appleby’s name, for, as 4 CAC’s commander, it was his responsibility to write Philip’s parents to express his and the unit’s condolences. He managed to talk his way past the guard and was escorted to the offices occupied by No. 4 Coastal Artillery Cooperation Flight and spoke to Appleby, the man who knew and led his son.

Certainly, Gordon Appleby was gentle and accommodating to the father of his lost pilot. He also knew the effort that Louis had made to get to Sydney, as he had made trips across the country to see his family in Chilliwack, BC, and his wife had joined him on several occasions when he was stationed at Dartmouth and Summerside, P.E.I.. She was now living in Sydney as Ida had done with Philip. The unit’s diary for June 16 recorded Louis’ short visit:

“Mr. Bosloy, father of F/O P. Bosloy who was reported missing February 24th, called at the Station today and was speaking with F/L G. W. Appleby It appears Mr. Bosloy has had a dream three nights in succession in which his son appeared to him and told him that he, his son, was on an island, alive, but unable to reach the mainland. Mr. Bosloy is convinced his son is alive and desires the Air Force to keep an extra sharp look out while flying.”

I cannot determine if Louis then turned around and headed back to the train station, having said his piece, or if he visited the various police services in the area to share the story of his dreams. While the RCAF military police had oversight of the station, the municipalities of Sydney, North Sydney, and Glace Bay all had their own police services then (they are all amalgamated into the Cape Breton Regional Police today), and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) covered the rest of the island. An article the next day in the Ottawa Journal indicated he was questioning locals about what they knew of his son’s disappearance:

“Father Refuses To Abandon Hope for FO. Phil. Bosloy

Sydney, N.S. June 16.—(CP)— Still hopeful that his son is alive even though he was reported missing three months ago when an R.C.A.F. aircraft disappeared in this area, Louis Bosloy, of Ottawa, has arrived here to renew the search for FO. Philip Bosloy.

FO. Bosloy 22, and Flt. Sgt. J Flabick [sic], of Estevan Sask. were occupants of a plane which was flying from Scoudouc, N.B., to this city. The plane was sighted here early one evening, but failed to make a landing. [Ed: No report of this sighting is noted in the 4 CAC ORB, or following investigation report]

Mr. Bosloy is confident his son is safe on some isolated island off the coast near here. He is questioning coastal residents and appealing to the R.C.A.F. to make another attempt to locate the men. An extensive search was carried out at the time the plane was first reported missing.”

Perhaps he got a hotel room and lingered in the area hoping to learn more and understand what happened that day in February. It wasn’t long, however, before he returned to Ottawa to pick up the pieces of his life. But then, two weeks later, something strange happened.

The Phantom

In the late afternoon of Saturday, July 3, the municipal police service at Sydney received information from a local by the name of Arthur McInnis, of McLeod’s Crossing, that “He had seen a man dressed in Air Force uniform, heavily bearded, hair tangled, no cap, uniform very ragged at about 0300 hours when he was proceeding to work on the morning of the 3rd”. A patrol of two policemen was sent to the area to investigate. By the time they stopped their search, it was near midnight and they had found nothing. As the next day was Sunday, nothing further was done about the sighting until Monday the 5th. Again it was a late afternoon to late evening search and it turned up nothing.

On Tuesday, July 6, at about 4:45 a.m., three young boys: 10-year-old Bobby Wilton, 11-year-old George Allen, and 12-year-old Michael Boyce, came into the Glace Bay Police Station to report “That while they were in the woods today, near Crowe’s Pond about 1530 P.M., they saw a man in the woods, they think he was an airman, he had on a coat with wings on the right side, no cap, his hair was all fuzzed up, he had a heavy whisker around his face. They were only five or six feet from him, the little boys shouted at him and he started running, then he hid from them behind a tree and watched them.”

A patrol was made that day (July 6) by five RCAF service police, including an investigator from the RCAF Provost and Security Services. They were on foot and in a patrol car, but once again nothing was found. While they were searching, the city police received a further report from a Mrs. Jones on Highland Street on the west side of Glace Bay. She said she saw an airman “acting in a peculiar manner along the R/R track about 500 yards from the front of her house,” at about 5 p.m.. She said the airman came out of the bush, walked along the track for a short distance while constantly looking back over his shoulder. He then turned around, walked back to his starting point and re-entered the bush. Police searched the area, questioning some berry pickers who were in the same area, and no one else reported seeing the phantom airman. The next day, another search was carried out by Glace Bay City Police, The Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and civilian volunteers, but no sign or even rumour was found.

By now, the story about the airman was spreading and an article had already appeared in the Post Record, Sydney’s daily newspaper. A Mrs. MacNeil, perhaps a Sydney neighbour of Philip Bosloy and his wife Ida, sent the news clipping to Ida or Louis Bosloy who were now back in Ottawa. On July 8, an Article appeared in the Ottawa Journal:

“His Hopes Revived Airman Son Alive

Louis Bosloy, 885 Bank Street, has had his hopes renewed that his son, Flying Officer Philip Bosloy, missing since February 24 on a flight from Scoudouc, N.B. to Sydney N.S., may be alive.

Newspapers of the last few days have carried reports that a bearded man wearing part of an Air Force uniform has been seen twice in the woods near Glace Bay. Mr. Bosloy thinks he may be his missing son despite the fact that the air force officials hold faint hope that the young officer may have lived through the Winter in the woods. Mr. Bosloy received a clipping from the Sydney Post Record sent by Mrs. James L. MacNeil carrying reports of the strange airman. Mr. Bosloy is certain his son is alive.”

I seems that Louis Bosloy had contacted the Ottawa newspapers, perhaps to enlist their support through public opinion to put pressure on the RCAF to reopen the search.

The RCAF police investigator carried out unsuccessful searches and interviews in the area on the 8th, 9th and 10th along with every airman and army service personnel who could be spared from his or her regular duties and members of all available police services. Nothing could be found since the phantom’s last appearance on July 6. No further searches were made, but a week later, on July 13, Louis Bosloy stepped off the train at Sydney train station and took a cab to the air station. It was his second visit from Ottawa in a month.

One can only imagine the contrast in the commander’s office between the police who had found nothing for the last week and who had many other things to do, and the desperation and fragile hope of Louis Bosloy. The investigator’s word’s tell us everything:

Mr. Bosloy… visited the station convinced that the reported airman was his son. While it was not intended to destroy this rather fantastic and impractical belief, it was pointed out to Mr. Bosloy that there were very few facts connected with the case and that for the most part it consisted wholly of rumour and the police were considering abandoning the case.

However, the utmost co-operation was extended to him, and accompanied by F/O Saunders, and Cpl. Hicks he was taken into Glace Bay to interview Chief of Police McGinnis and the R.C.M.P. in order to obtain the latest information regarding the missing airman.

The next day, Bosloy was back at the air station where he was shown reports demonstrating the actions undertaken in the case. He was also informed that any further extensive search would have to be dependent on reliable information. It would be impractical to make small haphazard searches of such extensive territory. Just as they were gently letting Bosloy down, another rumour surfaced in the afternoon of the 14th.— “That an airman had come to the back door of a house near No 11 Colliery asking for something to eat. The lady of the house, Mrs Buchanan, gave him some food in the kitchen and slipped out to get some help, but when she got back the airman was gone, taking the food with him.” Flying Officer Saunders, along with the Provost investigator and a member of the City Police escorted Bosloy to the location near No.11 Colliery to investigate. While interviewing people in the neighbourhood they ascertained that the rumour of the airman was concocted by some children who had been left alone in a house to play. They had gone out for a while and had forgotten to close the door. They made up the story based on the recent phantom airman stories to cover the fact of leaving the house wide open.

While all this was happening in Cape Breton, the July 14 Ottawa Journal reported:

“Louis Bosloy Reaches Glace Bay To Hunt For Son

GLACE BAY, N.S. July 13 (CP)—Louis Bosloy, of Ottawa who believes his missing R.C.A.F. son is alive somewhere in the Cape Breton area, arrived today to investigate reports that a raggedly clad flyer has been wandering about a wooded area near here.

It was the man’s second visit to Cape Breton in search of his son—FO. Philip Bosloy—who vanished in March [sic] on a flight to Sydney, N.S., from Scoudouc, N.B.. The father came here last month expressing belief FO. Bosloy was marooned on some island off Cape Breton.

A few days ago, he read reports that residents of nearby McLeod’s Crossing had seen a young airman roaming the woods there. The residents told police that, on different occasions the flyer has been seen on the fringe of the woods, invariably dashing back among the trees when sighted.

Search parties have combed the area, without finding any trace of the man.

Bosloy conferred today with officers of the Cape Breton airport and with Chief of Police J. M. McInnis of Glace Bay. The police official said his department would co-operate in a search but added it was handicapped because of difficulty getting volunteers to cover the woods.

The next day, July 15, another rumour surfaced. It seemed an airman, matching the description of the wild-looking hermit, was seen nearby the farm of a Frank Holmes on Reserve Road. A youth by the name of Anne Murray, bringing in the cows, had seen him standing some 500 yards away. Because it matched the descriptions in other stories, it was deemed credible enough to conduct a thorough search the following day.

At 1:30 p.m. the following day approximately 60 airmen from Sydney’s air station were driven to the area near Holmes’ farm. Walking in a line and twenty feet apart, the airmen covered the area slowly, starting at McLeod’s Crossing, and coming out of the bush two miles past the Holmes farm. Nothing was found. An hour and half after the airmen started, 50 soldiers from Sydney’s army detachment made a similar sweep on the north side of Reserve Road, searching the wooded area along the way. The results were the same as always.

While the groups were sweeping the area, F/O Saunders and the Provost investigator paid a visit to Holmes’ neighbour, a chicken farmer by the name of McAuley. At the back of his chicken barns they found several large rain shelters that were no longer in use. In the one farthest from the farm house, they found evidence of recent occupation as the grass inside was flattened where someone had been sleeping with a pile of old burlap bags as a pillow. McAuley stated that the shelter had been abandoned and unused for some time. It was McAuley’s opinion that this was the resting place of the hobo known as the “phantom airman”. Two police officers waited in the shelter in the hopes the phantom would return, but left after midnight on Saturday morning.

On Saturday 17th, Louis Bosloy himself, along with two other volunteers, arrived at McAuley’s farm and encamped in the shelter, where they spent the entire night waiting for the return of the phantom. One can only imagine what went through Louis Bosloy’s heart and mind throughout the night as he lay there listening to the wind and the sounds of the nearby woods, his heart pounding with every strange sound, feeling closer than ever to finding his son. It breaks one’s heart to feel the anxiety, desperation and unrequited hope that lived in that space that night. Bosloy had placed all of his remaining hope to see his son again on the story of the phantom airman and surely could feel it all beginning to turn to dust on the wind. When morning came, the McAuley’s roosters crowed, the sun rose, the heat returned, but no one came.

There also seemed to be some aerial activity from the station. On Monday July 19, a report came in from the Aircraft Detection Corps, a military-run, civilian volunteer organization dedicated to spotting and reporting the movements of aircraft in the skies over Canada — a sort of unpaid, Mk I Eyeball, distant-early-warning system in the age just before radar. The report spoke of an unidentified crashed aircraft in the Margaree River area, some 80 kilometres due east of Sydney near the mouth of the Northumberland Strait. On July 19th, 4 CAC made one of its Lysanders ready and a sortie was made by Flight Lieutenant Appleby and Warrant Officer Seaby to the Margaree River area to search for the reported aircraft. Nothing was found despite a two-hour aerial search.

On the 20th, the Provost investigator visited the Glace Bay police station to hear details of another rumour. A 14-year old boy by the name of Lloyd McKay claimed to have spotted the airman on the Reserve Road the day before and that the airman had an identity disc around his neck with numbers on it. Police did not give him much credence, but news travels fast, for on July 20 (the same day), the evening Montreal Gazette reported:

“HOUND TO TRACK GLACE BAY HERMIT

Louis Bosloy, of Ottawa, Hopes Man May Be Missing SonGlace Bay, N.S., July 19—(CP)— Glace Bay’s phantom of the woods turned up again today, and his latest appearance prompted authorities to try to enlist the services of a bloodhound to track down the mysterious hermit who has been lurking in a nearby wooded area for weeks.

Arrangements were being made tonight to bring in a dog from Moncton, N.B., to supplement the work of searchers who have been combing the woods for several days in quest of the unkempt, semi-clad man, said to be dressed in the tattered remnants of an airman’s clothing.

Louis Bosloy of Ottawa arrived here several days ago in the hope the man might be his R.C.A.F. son, FO. Philip Bosloy who disappeared on a flight over this area in March. Today, 14-year old Lloyd McKay reported he had seen the hermit and approached closely enough to ask if he was the missing airman.

“What airman?” he quoted the man as saying before he dashed back into the bush.

Young McKay said the man had long hair and a bushy beard, and was bare from the waist up. He said he had an article hanging from his neck that looked like an identification disc.

After checking in at the Holmes farm that day, the Provost investigator spoke to Mrs. Holmes who did not hesitate to give her thoughts on the whole “phantom airman” thing, telling him that “There were many rumours going about the district concerning the airman but there was little or no truth in them, most of them being started by children and passed on by adults who should know better.”

On Wednesday, July 21st, the investigator along with a Public Relations agent from Eastern Air Command of the RCAF, both of whom were concerned about the phantom airman sightings spiralling out of control, were called to the Glace Bay police department where they were told by the Chief that the airman seen in the more recent sightings was Aircraftman Second Class (AC2) J. Donovan (service number R213208) home on leave from his unit at No. 8 CMU (Construction Maintenance Unit) at Tuft’s Cove in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. He stated that Donovan had told his mother about seeing the boys in the woods and that they had asked him if he was the lost airman and that he had jokingly replied that he was his brother. Donovan’s home was just half a mile from the wooded area where the boys saw him and he confirmed that he was shirtless when the boys saw him. The Chief also informed him that the local Boy Scout troop was planning to make a search through the bush the following day and that Army units were planning to hold exercises in the same area in the hopes of also finding some trace of the elusive phantom. He said it was not necessary for the RCAF personnel to be called upon. The story of Donovan’s interaction with the young boys reached Canadians across the country and began to unravel the groundswell of support for the theory that the phantom airman was Philip Bosloy. The Sydney Post Record that evening reported the Donovan explanation for the phantom, stating at the very end:

“It now develops that much of Mr. Bosloy’s confidence that the man is his son, has been based on a series of dreams which he had some time ago that the youth is marooned on some island in the Atlantic region. He has also consulted some fortune tellers who have bolstered his confidence considerably, it was learned today”

Over the next couple of days several cities across Canada published stories that backed down from the theory of Bosloy as the phantom. The Regina Leader Post put a nail in the coffin for Louis Bosloy:

The “phantom airman” supposed to be haunting the woods around Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, has been run to earth. He’s AC2. J. Donovan, stationed near Halifax, with the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was taking an innocent sun bath in the woods while on leave. This puts a crimp in a story that a survivor from a missing plane might be wandering dazed in the bush.

But the police are still on the lookout for a possible “hermit”.

The “phantom airman” story got out when four Glace Bay youths reported they saw a bearded man in the woods wearing an identification tag around his neck who fled at their approach.

Now, Donovan reports one of them asked if he was the phantom airman and he jokingly replies: “No, I am his brother.

The revelation now punctures the hopes of Louis Bosloy of Ottawa, who has been taking part in the search for a “phantom” in the belief that the “phantom” might be his son, Flying Officer Philip Bosloy, whom he dreamed was still alive.

I bring up the story from the Regina newspaper, to highlight the point that, at no time in the aftermath of the loss of Lysander 459 or the search for the “phantom airman”, did anyone ever mention John Slabick, the radio operator who also had disappeared with Bosloy. No one, not even the Saskatchewan newspapers, ever wondered if it was Slabick who was lurking in the bush around Glace Bay instead of Bosloy. Such was the power of Louis’ story to capture the public’s imagination

For several days, Louis Bosloy had been petitioning authorities to enlist the help of a scent hound to track the occupant of the shelter at the back of the McAuley chicken farm. The hoped-for dog from Moncton, New Brunswick never materialized, but Louis kept the pressure on. He was becoming more desperate by the day and began hounding both the local police services and the RCAF. On Thursday, July 22, Bolsoy, accompanied by Saunders and the investigator, visited the RCMP offices in Sydney with the intent of further pressure for police dogs. The lead investigator from the RCAF Provost services who later wrote the final report on the case stated that:

“It had previously been explained to Mr. Bosloy that it would be impossible for a dog to pick up any trail as old as the one left in the rain shelter at McAuley’s farm, and that it would be foolish to put too much faith in the dogs. Inspector Evans [Officer Commanding RCMP division at Sydney] tactfully informed him of these facts in the interview, but due to Mr. Bosloy’s state of mind and obsession on the subject, the inspector promised to do his best to bring one of these dogs down from Ottawa. Not, as he explained to us later, that the dog would be of much practical use, but that it would assure Mr. Bosloy and the Public that everything possible was being done to bring this search to a successful conclusion.

The arrival of Mr. Bosloy and the resultant publicity have built the first simple rumour up to such an extent as to become ridiculous except to the public mind. Public opinion being what it is, it is felt that the rumour will run its course until it finally dies a natural death. All three Police forces being extremely skeptical of the whole affair.

On the July 24, however, there was a secondary report from the Aircraft Detection Corps (ADC) of an unidentified crashed aircraft in the Margaree River area. Again Appleby made two flights over the area but nothing was found. On the same day, a delegation from the ADC came to Sydney and inspected a Lysander on the Parade Ground, perhaps to decide if that’s what had been seen. On the 25th, another search was made by Appleby of the Margaree area with the same results. There is no further explanation in the ORBs of what the ADC had seen.

As the search was winding down, the provost investigator spoke with the Chief of Police in Glace Bay on the 26th. The chief stated that he “was more dubious than ever that there was an airman wandering at large.” However, the long-awaited police dog from RCMP headquarters in Ottawa had arrived by train and he “considered it expedient to continue the case until all doubts were removed from the public mind.”

On the same day, he visited the RCMP Detachment at Glace Bay where he read their report on the case. That report expressed the opinion that “while the RCM Police were very dubious that such a figure as the mysterious airman existed, it would be most unfortunate if at some later date a body were found, thus bearing out the rumour, therefore every effort must be put forward so as to leave no doubt that everything possible was being done to find the rumoured airman.”

The last entry in the investigator’s report states that the Chief of Police gave a statement to the press announcing that “the search was being abandoned as he was firmly convinced that there was nobody lost or in need of help in the woods in this vicinity. With this official statement by the Chief of Police on the file, this case may be considered closed, the arrival of the Police dog from Ottawa has effectively stopped the occurrence of any further rumours on the subject, although a request has been made in the Glace Bay Newspaper, July 29, [likely placed there by Louis Bosloy] requesting anyone who sees the mysterious airman to report it promptly to the Police in order that the dog will have a hot trail to follow. Nothing more has been heard of, however.

Aftermath

On September 03, 1943, the United Synagogues of Ottawa held a service at Agudath Israel Congregation on Fairmont Avenue to remember members of Ottawa’s Jewish community who had died in the war — including Joesph Ash, Philip Bosloy, Jack Cooper, Jacob Galt, Harold Glatt, Stan Harris, Harry Levine, Philip Miller, Albert Schwartz, Sydney Slover, Herbert Wolf, and Moses Zumar. Sadly, there would be others who were added to that list by war’s end.

In November, the Ottawa Journal published a short courtroom item about Louis which reflects on his state of mind following Philip’s disappearance:

“Ottawa Man fined For Breaking Ceiling

“He had just returned from Cape Breton Island, where he aided in the search for a son in the R.C.A.F., missing since last summer [sic]”, T. P. Metrick, defence counsel told Magistrate Strike this morning in mitigation of Prices Board charges against Louis Bosloy, fruit store operator at 885 Bank Street, Ottawa.

Bosloy was convicted and fined $15 and costs on two charges of selling potatoes and oranges above ceiling price. Mr. Metrick said his client was in an upset condition after returning home, and had made a mistake in pricing two grades of oranges.

Investigator B. T. Watley said Bosloy had been warned by letter and personally that he was charging two cents above the ceiling price for on five-pound bags of potatoes. He stated the oranges were sold two cents per dozen over the top price for a certain grade.

It’s difficult to wrap my head around why he was not cut some slack for the sacrifice he and his family made that year. The loss of his son, the haunting of his dreams, the search of the woods and the nights spent listening for his son to return surely had broken his focus on his work.

Six months after the disappearance of her husband, Ida wrote to the Department of Defence, asking what she should do next:

“To date, I have received no official communication in this connection, and as I have been advised by friends that after a period of six months have elapsed, matters of this nature are automatically handed over to the Department of Pensions and National Health, I would appreciate it very much of you would kindly advise me of what action I should take in this connection and if I am to communicate with the department of Pensions and National Health, or if they will communicate with me in due course.”

Ida remained with her parents on King Edward Avenue, but eventually married Joseph C. Gold in 1946 and moved with him to Toronto.

On Thursday, August 19, 1948, five years after his son vanished, Louis Bosloy attended a professional wrestling match at the Auditorium, Ottawa’s major indoor arena, on O’Connor Street. The night’s card promised to be an exciting distraction for the man, still grieving over Philip’s disappearance. The match featured Ray Eckert (AKA Floyd Diefenbach) of St. Louis fighting “smooth” Pete Peterson, a former pro baseball and football player. European champion Yvar Martinson was slated to battle Enrique Torres, the Mexican Champion. In the highlight of the night, big game hunter “Touchie” Truesdale wrestled a 200-pound alligator he captured in a Florida swamp—“a savage animal which fights furiously, with claws and teeth”. It was a loud and boisterous evening in the blue smoke-filled and darkened Auditorium. In all the excitement, Louis suffered a massive heart attack while in his seat and was rushed to the Ottawa General Hospital, where he was pronounced dead. He was 63-years old. The Ottawa Journal reported that “The elderly man became particularly well known throughout Ottawa in March, 1943 when he made several trips to the East Coast to search for his son FO Philip Bosloy, who was reported missing after air operations from Sydney, NS on February 24 of that year.”

The Ottawa Auditorium, where Louis Bosloy’s suffering finally came to an end. Photo: Lost Ottawa

Louis (Boguslavsky) Bosloy came to Canada in 1913 at the age of 28 years with his wife Chawa and three-year old daughter Mary to offer a better life to the family he hoped to create. Had he remained in Ukraine, there is no doubt in my mind that he would have lost his entire family in the Holodomor terror-famines before the war or in the Holocaust itself. As it was, he still forfeited one of his sons to defeat the brutal and murderous Nazi cancer that laid waste to his homeland. Despite the statistical truth that his family avoided annihilation by emigrating, it was no consolation for a man who loved his boy so deeply. He did not rest until every ember of hope was extinguished, whether it was fanned by dream or rumour, by public opinion or media coverage. Like the families of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370, he held on to the faintest filament of hope and he took a longing for an explanation to his grave. He was buried south of the city in the Jewish Memorial Gardens on old Highway 31. Chawa was laid to rest next to him 20 years later.

Louis and Eva (Chawa) Bosloy’s shared headstone at the Jewish Memorial Gardens cemetery in south Ottawa. The epitaph for both Philip’s parents tells us everything we need to know about their priorities in life. For someone like Louis who lived and laboured for his family, the loss and vaporization of his son must have burned a hole in his heart from which he never recovered. Photo via Jewish Memorial Gardens

Living in Summerberry, Saskatchewan, Frank and Victoria Slabiak were far from any media attention with regards to their son’s disappearance. There is little to nothing to be found in the Saskatchewan papers about their son’s fate or their own grief, but I know they felt it as deeply as Louis did the loss of Philip. Their’s was the silence and anonymity of a family out on the prairie. Their grief had to be swallowed and the acid taste endured for the rest of their lives.

Philip Bosloy and John Slabick have no known graves. The only place where they are memorialized is on the bronze panels of the Ottawa Memorial on Green Island, overlooking the Ottawa River. The water below the Memorial flows forever eastwards to the St. Lawrence River and then down to the Gulf of St. Lawrence and on out to the cold North Atlantic where, far below, rest the undiscovered remains of Lysander 459.

Dave O’Malley

Philip Bosloy and John Slabick have no known graves. In lieu of a headstone, their names are inscribed on the bronze panels of the Ottawa Memorial. Photo: Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Neighbourhood of Ghosts

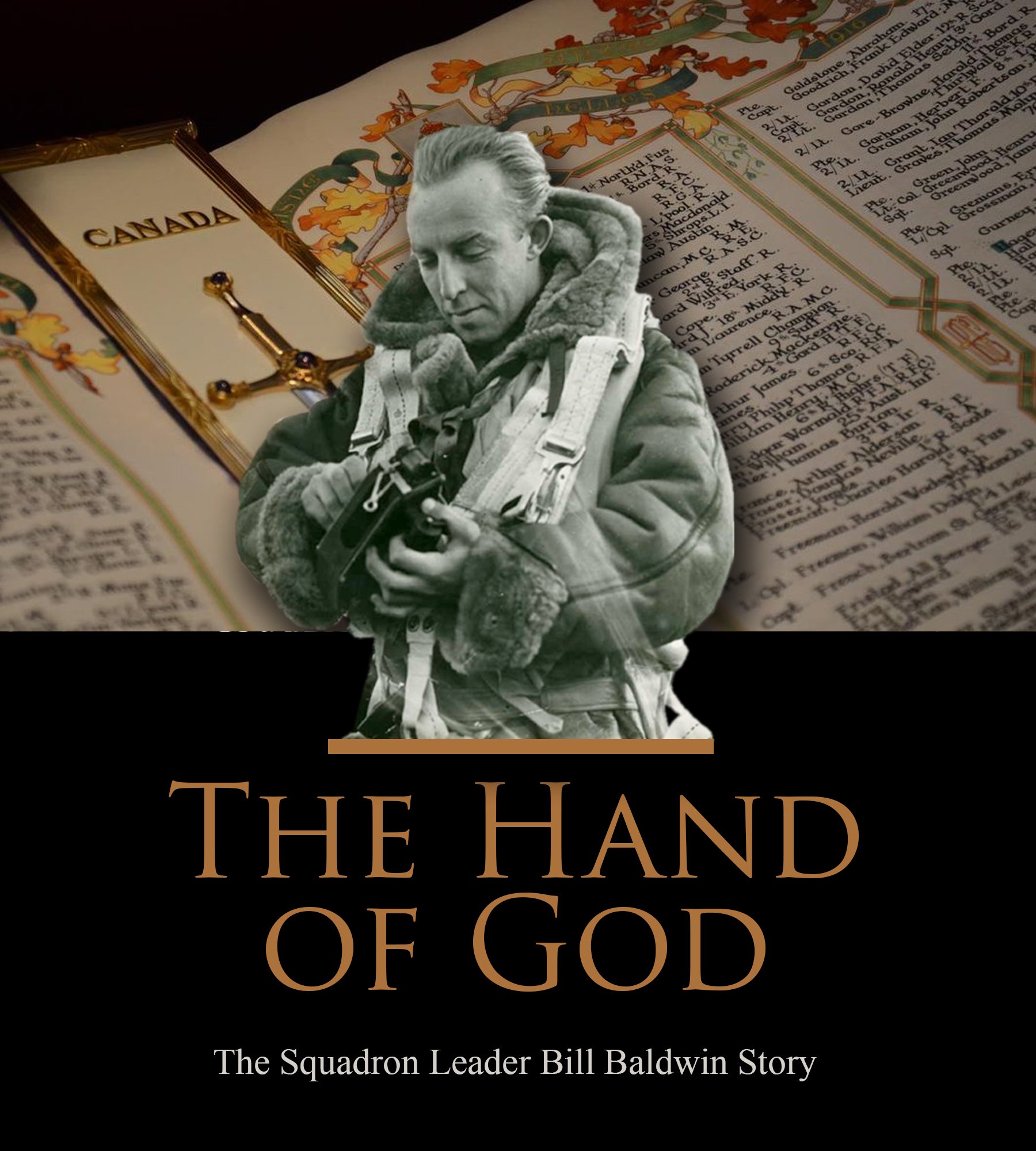

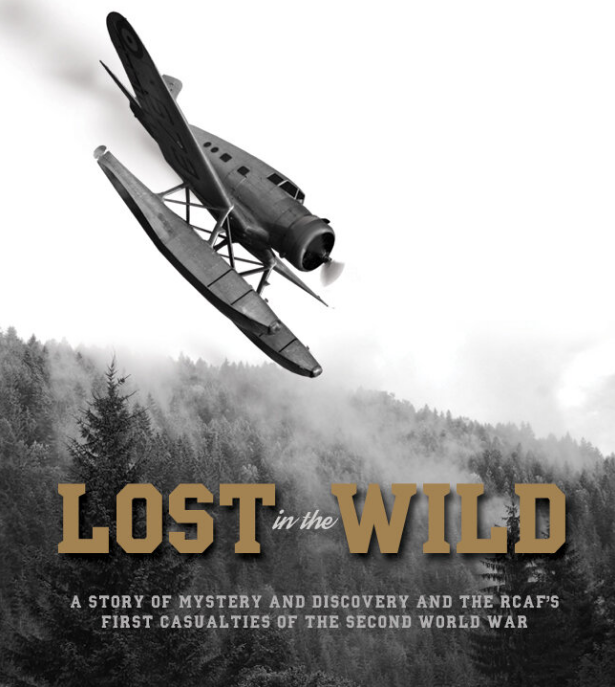

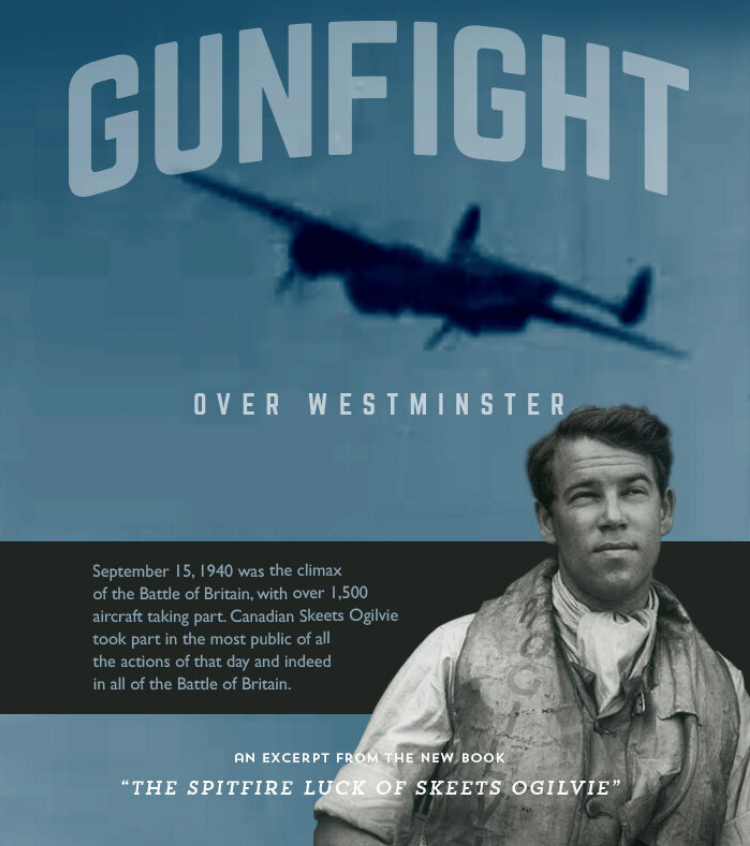

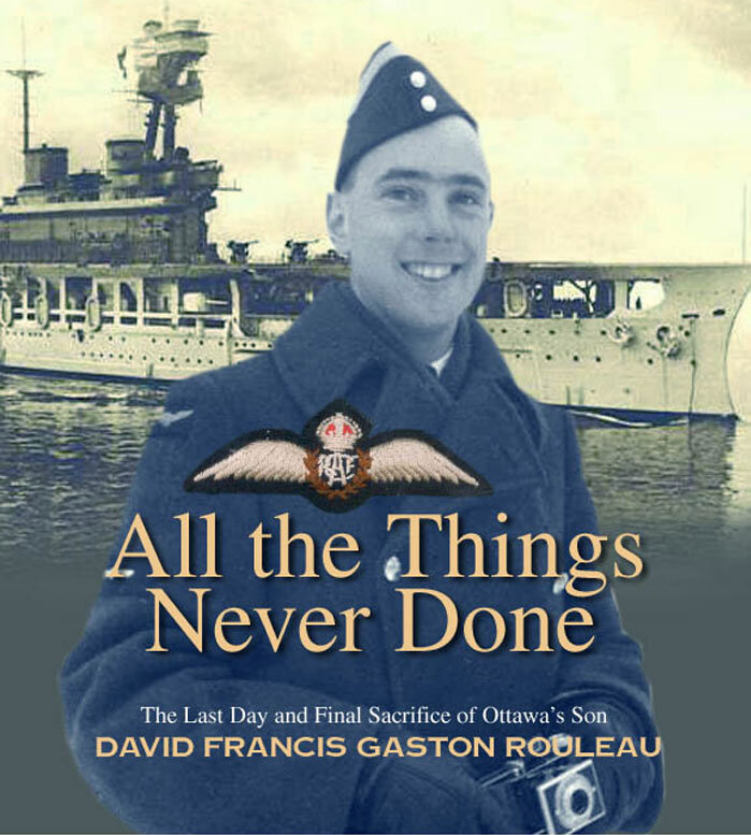

To read other stories of sacrifice from the Glebe neighbourhood of Ottawa, Click in an image